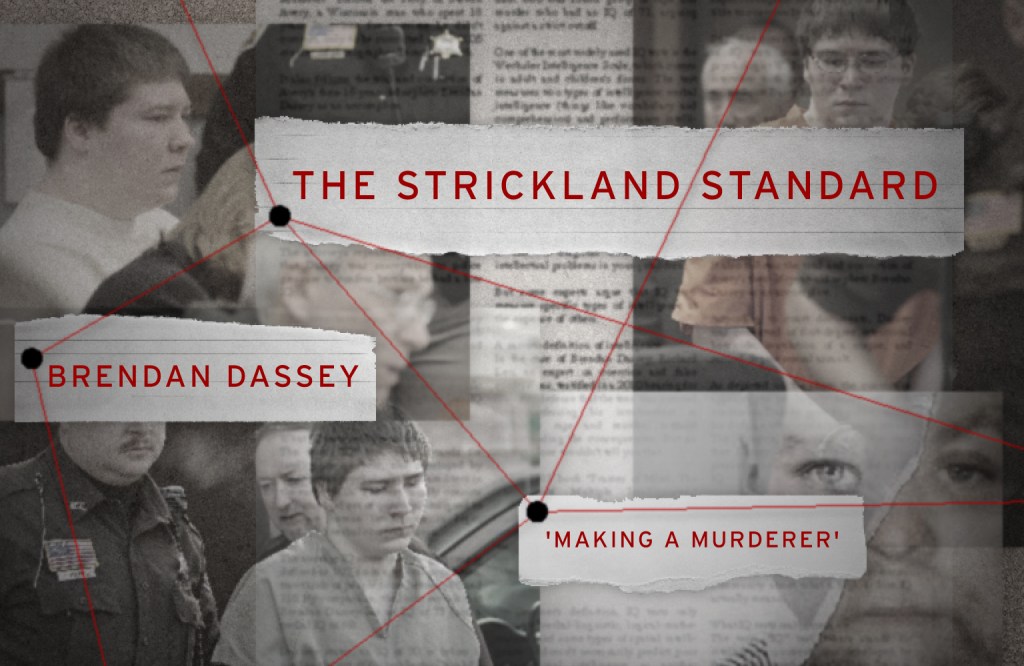

Understanding Brendan Dassey’s Sentence: ‘Making a Murderer’ and the Strickland Standard

The promise that everyone is equal before the law is a broken promise for the poor. – Professor Peter Joy

Anybody who has ever watched a crime drama is familiar with the Miranda warning, which informs defendants of their Fifth Amendment right to remain silent and their Sixth Amendment right to an attorney.

But, how good of an attorney does the Sixth Amendment guarantee and at what point is a lawyer’s performance so poor as to render the representation ineffective?

The U.S. Supreme Court answered these questions in 1984 with its ruling in Strickland v. Washington, which established the benchmark for ineffective counsel referred to as the Strickland standard. The recent Netflix documentary “Making a Murderer” brings the issue of effective representation squarely to the forefront.

The Conviction of Brendan Dassey

“Making a Murderer” tells the story of Steven Avery, who spent 18 years in prison for a sexual assault he did not commit. He was exonerated in 2003, when new DNA technology proved another man committed the crime. In a turn that makes his case compelling, Avery was charged with murder just two years after his release. He was eventually convicted, but the documentary shows his attorneys providing an exceptional defense. It is the representation of his nephew Brendan Dassey that warrants a discussion of the Strickland standard.

Soon after Avery’s arrest, Dassey was implicated as an accomplice to the murder. From the start, Dassey’s interrogation, confession and arrest were troubling. The documentary shows how the 16-year-old high school student was yanked out of class, interrogated four times over a period of 48 hours, questioned by police officers without his parents or an attorney present, and ultimately coerced into confessing.

The videotape of the police interview is agonizing to watch. With an IQ in the intellectual disability range, Dassey appears confused and easily manipulated by law enforcement officers. He seems eager to please his interrogators and ready to repeat details they feed to him so he can get back to class. This is a common pattern found when people confess to crimes they have not committed — the police interrogation is prolonged and manipulative, and they confess in order to stop the interrogation.

(Un)equal Before the Law

By Professor Peter Joy

The lack of adequate funding for public defenders at the state and local levels is undermining procedural justice for the accused, such as Dassey, and the rule of law in municipal, county, and other state courts. As a result of poor funding for public defenders and the almost impossible Strickland standard to prove your lawyer was ineffective, the promise that everyone is equal before the law is a broken promise for the poor facing criminal charges.

The Gideon opinion states, “Lawyers in criminal cases are necessities, not luxuries.”

Now, 50 years after Gideon, poor defendants are finding that although they have lawyers, it is still a luxury to have a lawyer with the time and resources to represent them in a truly competent manner. Until state and local governments provide sufficient funding for public defender systems, there will continue to be troubling cases like Dassey’s.

More disturbing, however, is the footage of Dassey’s former attorney Len Kachinsky and his private investigator. Criminal defense lawyers have a duty to act as zealous advocates for their clients. Instead, Kachinsky is shown in the documentary supporting the prosecution’s case.

The lawyer pressures his client to plead guilty. His private investigator coaches Dassey into a confession, which included gruesome drawings of the alleged crime scene. Kachinsky then arranges a meeting with police officers so they can question Dassey without a lawyer present. In the end, Dassey was convicted of first-degree intentional homicide and sentenced to life in prison.

If Brendan Dassey’s attorney was not considered ineffective, then how egregious does the representation have to be for the Strickland standard to apply?

Strickland v. Washington

In Strickland v. Washington, the defendant pleaded guilty to murder and was sentenced to death. He argued on appeal that his attorney delivered ineffective counsel when he failed to present mitigating evidence at his sentencing hearing that could have spared his life.

The U.S. Supreme Court found that, “The benchmark for judging any claim of ineffectiveness must be whether counsel’s conduct so undermined the proper functioning of the adversarial process that the trial cannot be relied on as having produced a just result.”

Based on this finding, the court established a two-pronged test to determine whether the attorney’s conduct met the benchmark for ineffectiveness:

- Did the attorney provide “reasonably effective assistance” considering the totality of the circumstances?

- Is there a reasonable probability that, but for the attorney’s ineffective assistance, the outcome would have been different?

In Dassey’s case, the Wisconsin appellate court rejected his argument that his attorney was ineffective. The court found a strong presumption that Dassey’s lawyer, “rendered adequate assistance and made all significant decisions in the exercise of reasonable professional judgment.”

Having ruled Dassey did not meet the burden on the first prong, the court did not consider the second prong of the Strickland standard.

Unequal Assistance of Counsel

More than 50 years ago, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Gideon v. Wainwright that the state must appoint an attorney to felony defendants in need of council. This ruling, in essence, required states to establish public defender systems that, when financially supported and staffed by competent attorneys, successfully protect the rights of defendants.

Unfortunately, defendants who must rely on a public defender system must often accept underfunded attorneys who deliver ineffective counsel because their huge caseloads cause them to be poorly prepared.

This was surely the case for Dassey.

Washington University School of Law Professor Peter Joy explains this inequality in his research paper “Unequal Assistance of Counsel”:

There is now, and has always been, a double standard when it comes to the criminal justice system in the United States. The system is stacked against you if you are a person of color or are poor… . The potential counterweight to such a system, a lawyer by one’s side, is unequal as well. In reality, the right to counsel is a right to the unequal assistance of counsel in the United States.

In theory, an objective application of Strickland v. Washington should correct this inequity. However, Joy contends, “As a result of the Strickland standard, only the most outrageous conduct by defense counsel leads to a new trial.”

Judging from the Dassey case, the bar for satisfying the Strickland standard is so prohibitively high as to perpetuate the systemic unequal assistance of counsel described by Joy. That Kachinsky’s representation passed muster demonstrates how Strickland v. Washington does not always guarantee a right to effective counsel.

Tweet this

The promise that everyone is equal before the law is a broken promise for the poor. – Prof. Peter Joy @WashULaw_Online #MakingAMurderer